W. E. Deming calculated that management is responsible for as much as 85% of all production problems and operators for only 15%. But as management, we expect our employees to keep working at a continually improving rate, while achieving the set specification of product. It is very easy for problems to occur, and the symptoms of these problems usually show up in the form of product inconsistency, a product that does not meet the agreed customer specification, late delivery, less/more than ordered quantity, or replacing of materials. But to find cause and take permanent remedial action requires a deep analysis and brainstorming sessions. Paul F. Bowes, Managing Project Director of Performance for Business Productivity Services Ltd., a manufacturing consultancy firm operating in the UK and Asia supporting the apparel industry, shares his experience on how some common problems were sorted out and never repeated again.

The apparel industry is not easy to work in. We ask human beings to continually make minute to minute decisions based on the many variable aspects of sewing two, or more, pieces of fabric together. It could be for numerous reasons like fabric is very difficult to handle, stitch count is not correct, there is oil leakage in the machine, needles are breaking, speed is uncontrollable, etc.

The Role of the Manager in Problem Solving

It is a known fact that lot of problems occur because the product specification is not complete or properly documented. For example – a boxer short which had side seams that were finished using overlock machine. The customer rejected the garment because the side seams should have been stitched with a twin needle machine. The method and garment specification stated only overlocking nothing more, nothing less. Who is responsible for the incorrect communication?

The management teams have to accept a change in the way they operate instead of playing a blame-culture game from – “Who did it wrong? and Whose fault is it?” to being a “How can we stop this from happening again?” culture.

Your role is to solve the problems that stop employees getting it right the first time, and to make sure that everything goes right so that employees cannot get it wrong.

Problem Solving Approaches

For every problem, there is a cause. It is management’s job to find the correct cause(s) as well as its solution so that the problem does not recur. The following techniques and examples are the key problem solving tools which need to be applied to move the organization forward, and the examples are taken from real effects that happened in MAS Holdings and Aitken Spence units in Sri Lanka, and garment maker SCAVI in Vietnam and Laos. These companies are committed to using these tools to find solutions.

[1] PDCA Cycle – Plan-Do-Check-Act (W. E. Deming)

Example – A shading problem occurred during bra manufacture with the two wings appearing to be different shades to the bra cups, using the same material (Figure 1).

Using the PDCA approach, the problem was tackled as follows:

Plan – The management team went to the operation where the problem was highlighted (gemba – actual problematic area), and reviewed the number of garments that appeared to be shaded. The physical movement of material was followed from the operator back to the cutting room and the steps involved and storage points were documented.

It was determined that not all but 50 garments were found having shading problems due to one or more of the following causes:

- Cutting section had placed wings from different parts of the lay into the box that was used to take cut parts to the sewing teams,

- Line leader had mixed up the wings and cups from the boxes when giving them to the sewing operators,

- Sewing operator had perhaps removed one defective wing and the counterpart, but the cups from the same ply were not removed, resulting in parts from different plies used on the same garment.

There was no numbering of individual panels for matching as it was considered as wastage, taking into account the quality of fabric supplied.

A plan was developed to tackle each of the potential causes:

- Each piece in the lay marker was clearly numbered during marker printing.

- After cutting, the extra process of ‘sorting’ was eliminated and the pieces were removed from the lay and straightway put into the transport boxes, thus reducing the chance of mix-up of pieces from different parts.

- The transport box (Figure 2) was segregated into sections and the wing and cup pieces were placed together in sectioned areas. This made it impossible to leave any piece of the garment out of the box.

- All defective parts were left in the bundle in the correct order, and immediate re-cuts requested (re-cuts were done at the start of the sewing team by the line leader), so that cups and wings would always be matched together correctly, even if removed later for completion of the re-cut work.

Do – The assigned team made changes within a day and management took a week to check and then QA carried it forward.

Check – The outcome of the changes was that the shading problem disappeared.

Act – There was no additional requirement for numbering every panel. If there had still been shading problems the PDCA cycle would have started again. The follow-up action from this exercise was to spread the same good practice across all teams and products.

[2] A3 Problem Solving (called A3 because that is the size of the paper used)

Example – Uneven leg hems on ladies underwear were a major effect being experienced in one factory. The leg hems measured differently from one side to the other (Figure 3).

The factory team used the A3 problem solving sheet (Table 1) to follow the PDCA methodology and identify an action plan to resolve the problem.

The area of the problem – “Uneven leg hems” was written in. The team went to the sewing floor to identify the operation at which the effect was occurring, “Top-stitch leg hems”. The effect or outcome was defined by writing in the product specification standard, and taking a photograph of the underwear with correctly balanced leg hems. This was shown by using a template. The team checked the visual balance and measurements of the leg hems before and after the operation. This was to ensure that the effect was happening at the topstitching operation and not at any prior operation, such as overlocking, or at cutting.

The target for improvement was set as reducing the variability of the leg hems to ± 2 mm within two working days of action plan completion.

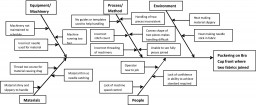

The potential causes were identified using the fishbone diagram (see Diagram 1):

- Material thickness variability causing machine running at slightly different speeds during the operation,

- Operator handling inconsistent from right to left leg caused by different method having to be used on each leg,

- Operator did not have any guides for achieving consistent leg hem size,

- Machinery used from one sewing team to another sewing team was of different brands, and also some machines were very old while the others were new.

The implementation plan consisted of reviewing the methods of all leg hem operators, identifying any sewing operators that were achieving consistent leg hem balance, videoing the “best” method, reviewing the method for incorporating any measure devices during the operation.

The new method was defined and implemented with one operator during the following two working days, and once consistency of output was established, all operators were trained in the same handling method. The mechanic team had to ensure that all machinery performed the same for handling.

In problem solving, the methodology of PDCA is supported by the A3 problem solving sheet (Figure 4), which is supported by the following key tools.

[1] Fishbone Diagram (Ishikawa Diagram)

Example – The puckering was visible on the front of the bra cups after two different fabric pieces were joined together and attached to the foam inner cup (Figure 5).

The fishbone diagram as shown in Diagram 1 was used along with brainstorming to come up with possible causes under the general headings.

Problem solving methodologies are supported by specific tools such as Fishbone diagram (Ishikawa Diagram), Brainstorming and Five why’s

[2] Brainstorming

The idea is simple, get your team together and write down as many ideas as possible without pre-judging them.

[3] Five Why’s

Example – An operator sewed the wrong size button onto the cuff of the shirt. Using the technique of “5 Why’s” we found the cause:

“Why was the wrong button sewn onto the cuff of the shirt?”

– “Because the operator did not have the correct size button.”

“Why did the operator have the wrong size button?”

– “Because the stores did not issue the correct button for the cuff, so the operator assumed that it was the same as for the front.”

“Why did the stores not issue the correct size button for the cuff?”

– “Because they thought it was the same size as on the front of the garment.”

“Why did they think it was the same size as the front of the garment?”

– “Because they did not check the specification fully and were rushing to issue the accessories as they arrived late.”

The examples are taken from real effects that happened in MAS Holdings and Aitken Spence units in Sri Lanka, and garment maker SCAVI in Vietnam and Laos

The effect was a simple error, but the causes meant that solutions had to be implemented as follows:

Short term fix: A template of the button sizes for the front and cuff for each garment size was placed on the operator’s machine. The operator checked that she had received the correct button sizes for the size of garment she was working on each time she got a packet of buttons from the stores.

Long term fix: Stores and Merchandising teams worked together to ensure that accessories were available at least two working days before they were required online.

Conclusion

It doesn’t matter how you capture the information. The key is to go to where the effect of the problem is – find out the current situation, measure it, identify potential causes and its solutions, create an action plan, and TAKE ACTION.

Once you have implemented changes, check to make sure that you are getting the desired effect, and if not, start again.

Finally, keep going. In our industry, everyday brings new and unexpected effects. If you can provide solutions, you will always be in demand.